Valerie Miner is the award-winning author of fifteen books. Her stories and essays have been published in more than sixty anthologies. A number of her pieces have been dramatized on BBC Radio 4, and her work has been translated into German, Turkish, Danish, Italian, Spanish, French, Swedish and Dutch. Miner has won fellowships and awards from The Rockefeller Foundation, Fondazione Bogliasco, The Brown Foundation, Fundación Valparaiso, The McKnight Foundation, The NEA, The Jerome Foundation, The Heinz Foundation, The Australia Council Literary Arts Board and numerous other sources, and has received Fulbright Fellowships to Tunisia, India and Indonesia. Since 2005 she has been Artist-in-Residence at the Clayman Institute. Bread and Salt is her fourth collection of stories.

Mary: Welcome to People Who Make Books Happen, Valerie. Let’s start at the very beginning: How did you become a writer?

Valerie: I started out as a journalist and reported from Africa, Europe, Canada and the US. Although I studied literature at university, we were rarely assigned books by women. When I later discovered books by Doris Lessing, Toni Cade Bambara, Bessie Head and Margaret Atwood, I began to dare to write fiction. My first co-authored book (1975) emerged from my writing group. I’ve been in writing groups ever since; they sustain and provoke my work.

Mary: Which writers have influenced you?

Valerie: I continue to be moved by the language of Shakespeare, Milton and Whitman, favorites since my U.C. Berkeley days. The feminist writers above inspire me as do Rohinton Mistry, Toni Morrison, Grace Paley and others who attend to the music of language and the challenges of fostering social justice and compassion. I’m grateful to my current writing group for close readings of Bread and Salt and to many other writers who “swap” drafts of new books with me. This kind of contemporary critique is crucial.

Mary: How do you get the initial idea for a story or novel?

Valerie: My novels are usually ignited by a question–a philosophical, spiritual, moral, political quandary. My stories are usually imagined from a particular scene. Place is very important in all my fiction.

Mary: Tell us more Bread and Salt. What is the most important thing readers should know about it?

Mary: The stories deal with women’s friendships, gun violence in families, falling in love, state terrorism, guardian angels, suicide as well as provocative encounters in India, Indonesia, Italy, Turkey and other places. The title novella follows two lovers from Tunisia to Boston to France and back to Tunisia. Three quarters of the stories feature queer characters. (Two of my previous collections were finalists for the Lambda Literary Award in Lesbian Fiction.) In a variety of forms ranging from mirco-fiction to novella, the characters in Bread and Salt navigate romance, terror, grief, passion, and whimsy.

Mary: If you could ensure that one of your stories would survive to be read 500 years from now, which story would it be, and why have you chosen it?

Valerie: If I’m brief, may I pick two? “Incident on the Tracks,” depicts a short train journey during which three strangers of various races, classes, ages and genders discover an unlikely friendship. “Hollow” explores the often ignored tectonic shifts within a family that can lead to catastrophe in our gun-obsessed culture.

Mary: Thank you for joining us here today, Valerie. Before you go, where can readers buy copies of Bread and Salt?

Valerie: Bread and Salt is available (in paperback and ebook) from independent bookstores as well as Amazon, B and N, etc. For book clubs who buy Bread and Salt, I’m happy to offer a gratis Zoom visit. I enjoy meeting readers and hearing their insights.

Valerie: Bread and Salt is available (in paperback and ebook) from independent bookstores as well as Amazon, B and N, etc. For book clubs who buy Bread and Salt, I’m happy to offer a gratis Zoom visit. I enjoy meeting readers and hearing their insights.

Links

www.valerieminer.com

Instagram valerieminer1

One of the most important influences on my development both as a poet and a novelist are two letters written by the English poet John Keats in 1818. In the first letter, addressed to his brothers George and Tom, Keats develops the concept of “Negative Capability,” which he defines as the ability to “remain in uncertainty” as one writes. I believe that Keats has touched on something profound here that is integral to the creative process.

One of the most important influences on my development both as a poet and a novelist are two letters written by the English poet John Keats in 1818. In the first letter, addressed to his brothers George and Tom, Keats develops the concept of “Negative Capability,” which he defines as the ability to “remain in uncertainty” as one writes. I believe that Keats has touched on something profound here that is integral to the creative process. Mary Mackey’s original Chapter One essay

Mary Mackey’s original Chapter One essay  “

“ Charlotte: Mary, your new book,

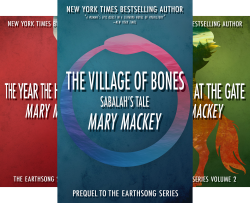

Charlotte: Mary, your new book,  Mary: Writing The Village of Bones was very different from writing the other three books in the series, because I had to constantly keep the plots of the other books in mind. The story unfolds twelve years before the the opening of The Year the Horses Came, which means that I couldn’t contradict anything I had said about the past in The Year the Horses Came, The Horses at the Gate, and The Fires of Spring. This presented some real challenges.

Mary: Writing The Village of Bones was very different from writing the other three books in the series, because I had to constantly keep the plots of the other books in mind. The story unfolds twelve years before the the opening of The Year the Horses Came, which means that I couldn’t contradict anything I had said about the past in The Year the Horses Came, The Horses at the Gate, and The Fires of Spring. This presented some real challenges. Mary: We don’t have any written history from 6000 years ago, but we do have the research of archaeologists, paleontologists, archaeomythologists, and other scientists and scholars. I drew on their findings whenever possible, because I wanted my readers to feel confident that they were getting as accurate a picture of the daily life of the Goddess people as they could have without actually stepping into a time machine. Whether I am writing about Europe 6000 years ago or Imperial Russia under the Tsars, my goal is always as much factual accuracy as possible.

Mary: We don’t have any written history from 6000 years ago, but we do have the research of archaeologists, paleontologists, archaeomythologists, and other scientists and scholars. I drew on their findings whenever possible, because I wanted my readers to feel confident that they were getting as accurate a picture of the daily life of the Goddess people as they could have without actually stepping into a time machine. Whether I am writing about Europe 6000 years ago or Imperial Russia under the Tsars, my goal is always as much factual accuracy as possible.

begins right after the end of The Village of Bones and relates Sabalah’s search for her lover, Marrah’s father. The second is a sequel to The Fires of Spring, which tells the story of Marrah’s return to her home in the hope of finding her mother Sabalah still alive after many years. Both novels are stories of love, quest, and reunion. My only challenge is to figure out which one to write first.

begins right after the end of The Village of Bones and relates Sabalah’s search for her lover, Marrah’s father. The second is a sequel to The Fires of Spring, which tells the story of Marrah’s return to her home in the hope of finding her mother Sabalah still alive after many years. Both novels are stories of love, quest, and reunion. My only challenge is to figure out which one to write first. Mary: I’ve gotten some excellent reviews, which is very important to the success of a novel. Many cite the same things that made the first three novels in the series popular with readers including praise for my historical research and pleasure in a vision of a peaceful society where children are cherished, men and women are equal, and people live in harmony with the earth. The reviewers have also said that The Village of Bones is lively and entertaining.

Mary: I’ve gotten some excellent reviews, which is very important to the success of a novel. Many cite the same things that made the first three novels in the series popular with readers including praise for my historical research and pleasure in a vision of a peaceful society where children are cherished, men and women are equal, and people live in harmony with the earth. The reviewers have also said that The Village of Bones is lively and entertaining.

Your unconscious is packed with ideas, metaphors, visions, plots, dreams, colors, characters, emotions—in short, everything you need to write a great novel or collection of poems. But how do you get to it? How do you step out of the social agreement we call “reality,” and dip into this incredibly rich resource?

Your unconscious is packed with ideas, metaphors, visions, plots, dreams, colors, characters, emotions—in short, everything you need to write a great novel or collection of poems. But how do you get to it? How do you step out of the social agreement we call “reality,” and dip into this incredibly rich resource?  Wednesday, September 21, 2016, Berkeley, CA: Celebration of the paperback edition of

Wednesday, September 21, 2016, Berkeley, CA: Celebration of the paperback edition of

A few months ago, I packed up six drafts of my recently published novel

A few months ago, I packed up six drafts of my recently published novel